Balanced budget

| Part of a series on Government |

| Public finance |

|---|

|

Optimum

|

|

Reform

|

A balanced budget is when there is neither a budget deficit or a budget surplus – when revenues equal expenditure ("the accounts balance") – particularly by a government. More generally, it refers to when there is no deficit, but possibly a surplus.[1] A cyclically balanced budget is a budget that is not necessarily balanced year-to-year, but is balanced over the economic cycle, running a surplus in boom years and running a deficit in lean years, with these offsetting over time.

Balanced budgets, and the associated topic of budget deficits, are a contentious point within academic economics and within politics, notably American politics. The mainstream economic view is that having a balanced budget in every year is not desirable, with budget deficits in lean times being desirable. Most economists have also agreed that a balanced budget would decrease interest rates,[2] increase savings and investment,[2] shrink trade deficits and help the economy grow faster over a longer period of time.[2] Within American politics the situation is much more debated, with all US states other than Vermont having a balanced budget amendment of some form, while conversely the US federal government has generally run a deficit since the late 1960s, and the topic of balanced budgets being a consistent topic of debate. In rare cases large budget surpluses may also be banned, as in the Oregon kicker.

Contents |

Economic views

Mainstream economics mainly advocates a cyclically balanced budget, arguing from the perspective Keynesian economics that budget deficits provide fiscal stimulus in lean times, while budget surpluses provide restraint in boom times.

Alternative currents in the mainstream and branches of heterodox economics argue differently, with some arguing that budget deficits are always harmful, and others arguing that budget deficits are both beneficial and in fact necessary.

Schools which often argue against the effectiveness of budget deficits as cyclical tools include the freshwater school of mainstream economics and neoclassical economics more generally, and the Austrian school of economics. Budget deficits are argued to be necessary by some within Post-Keynesian economics, notably the Chartalist school.

- Larger deficits, sufficient to recycle savings out of a growing gross domestic product (GDP) in excess of what can be recycled by profit-seeking private investment, are not an economic sin but an economic necessity.[3]

Political views

United States

In the United States, the fiscal conservatism movement believes that balanced budgets are an important goal. Every state other than Vermont has a balanced budget amendment, providing some form of ban on deficits, while the Oregon kicker bans surpluses of greater than 2% of revenue. The Colorado Taxpayer Bill of Rights (the TABOR amendment) also bans surpluses, and requires the state to refund taxpayers in event of a budget surplus.

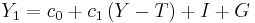

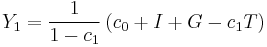

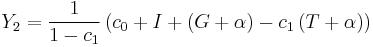

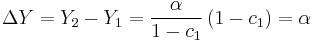

Balanced budget multiplier

Because of the multiplier effect, it is possible to change aggregate demand (Y) keeping a balanced budget. The government increases its expenditures (G), balancing it by an increase in taxes (T). Since only part of the money taken away from households would have actually been used in the economy, the change in consumption expenditure will be smaller than the change in taxes. Therefore the money which would have been saved by households is instead injected into the economy, itself becoming part of the multiplier process. In general, a change in the balanced budget will change aggregate demand by an amount equal to the change in spending.

See also

- Balanced Budget Amendment (United States government)

References

- ^ Sullivan, Arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics: Principles in action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 376,403. ISBN 0-13-063085-3. http://www.pearsonschool.com/index.cfm?locator=PSZ3R9&PMDbSiteId=2781&PMDbSolutionId=6724&PMDbCategoryId=&PMDbProgramId=12881&level=4.

- ^ a b c http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/budget/stories/050497.htm

- ^ (Vickrey 1996, Fallacy 1)

- Vickrey, William (October 5th, 1996), Fifteen Fatal Fallacies of Financial Fundamentalism: A Disquisition on Demand Side Economics, http://www.columbia.edu/dlc/wp/econ/vickrey.html. Paper was written one week before the author's death, three days before he received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.